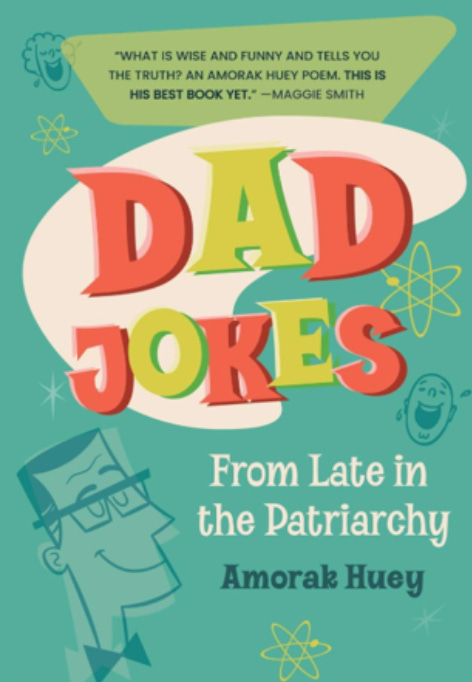

The limitations of Fatherhood are amplifications of the limitations of our humanity. This limitation along with both the struggle against and eventual resignation to it is the central point of reference in Amorak Huey’s poetry collection Dad Jokes from Late in the Patriarchy. I say resignation because Huey does not give up ground to the fatherly struggle easily in this body of work. Like previous Huey collections, Dad Jokes is laced with thoughtful humor in serious work, placing Huey firmly in the camp of contemporary inquirers like Mark Halliday and the late Tony Hoagland. But Huey’s humor goes deeper and darker than the standard ironic observation, breaking new ground in the explorations of the depths of the human condition. Dad Jokes from Late in the Patriarchy is the masterwork of a fine craftsman of contemporary American poetry.

The structure of Dad Jokes could be easily dismissed as too casual or offhanded for serious examinations of the self, of the relationship of fathers, or the culture. The manuscript is organized into four sections fashioned after joke structure: Setups, Reinforcements, Misdirections, and Punchlines. It is not until after the poetry within each section is examined that we realize that the titles of the four parts are their own form of wordplay, a dominant technique of the dad joke proper, albeit with an overtly dark sense of self-awareness. While the major theme does not stray much throughout the four parts from the initial Setup section there are markedly darker tonal shifts that stand in contrast to the feign of light-heartedness that Huey leads with, especially in the absurdist nature of his poems’ titles with their pop-culture-idiosyncratic juxtapositions. And what is the underpinning idea that Huey is advancing in this work? That we soon realize as fathers that our lives are dominated by disillusionment bordering on fatalism—hardly a laugh-out-loud moment.

Huey, as in all his work, is dealing in serious stuff. “America is fond of its rootles men” (p.15) he announces in Pa & Michael Landon & Buddy Ebsen & Daniel Boone. He confesses “I am somewhat embarrassed…to admit how much time I spend thinking about people who have more money than I do.” (p.23) in Fred Flintstone & George Jetson. He bluntly observes “It’s not profound/it simply is: what lives, dies” (p.24) in Fairy Tale, a poem title that belies the hard reality it explores. In these first poems, his humor is soft-edged, and we are comforted by both the intimacy of his first-person point of view and the authentic voice of that person. “Don’t kill the family is the only rule that’s written down” (p.27) from Steven Keaton & Dan Conner & Bob Saget & Alan Thicke & Both of My Two Dads (see what I mean about the titles) is funny in its dark reductionism, a technique he uses and amplifies throughout the entire book. This deployment of humor to reduce a personal truth or epiphany to its harshest dark place works beneath irony in that it cuts so deeply to our dark failures making us unsure of how to respond. Are we supposed to laugh? Were these lines simply ironic, our response would be predictable as we have become well-versed in the use of irony and the appropriate response to it. If this is irony in Huey’s work, then it is irony with a very sharp bite. Huey concludes his opening Setups with a line from his poem Elegy for Dr. Spock, “…the moral arc of the patriarchy is long & bends toward most of the damage has already been done.” (p. 34). The syntax playing here between present and past tense serves to land that line hard while simultaneously demonstrating the voice of a strong poet questioning everything—himself, personas, fatherhood, the role of humor, the role of thought—it’s all here.

Huey disperses poems of revealing couplets, mixed with tight-lined free-verse, along with a dabbling of prose to advance Dad Jokes forward, through, and down into his inquiry. The energy builds toward disassociation throughout the second section of the book, Reinforcements. In the poem The Seventh Anniversary is Salt & I Do Not Know a Gift for That Huey asserts “As a species we are notorious/for not knowing what we want.” (p. 45). In The Girl on the Unicycle he continues, “my life has not stopped feeling/like practice for some life/ that’s around the corner.” (p.55). In Section 3 of the volume, Misdirections he presses disassociation further with the poem Luminescence in the lines “How have ended up here? One accident/after another, that’s how.” (p.73). That line is so certain that it runs the risk of sounding pedantic. But Huey earns these lines in poems that drive the observation as a rational conclusion within the logic of his rhetoric.

The final section of the book is Punchlines, and this section title can be read two ways: as the punchline of a joke or as lines of poetry that punch us in the gut. In the title poem of the book Dad Jokes, the punches land in rapid succession along with a dark gallows-type humor that fully bares its teeth and bites down hard. The poem opens with the type of cornball dad jokes that we expect to hear, eye-rolls and all, but then turns toward the dark on the lines “What do you call someone/threatening to blow up Jewish daycares?” (p. 77). That move is so jarring, so attention-grabbing, so brilliantly revealing. Here the poem throws line-after-line of gut-punching social commentary from gun violence and election mistrust to the danger of the annihilation of individualism itself. Huey, like all great humorists, has a great sense of timing. He knows he needs to let us off the hook after this barrage, so he lightens the mood with the lines “I’m starting to dislike/this bartender.” (p. 77,78). The poem does not resolve in a happy light-hearted way when he admits that “At some point I came to understand/my job was to make the world/more bearable for my children.” (p.78). Is this pessimism? Realism? It sure isn’t a candy-coated naivety. It certainly is not highly aspirational—life as bearable, really? But it is an honest self-appraisal for a poet who rightly admits in Lifespan of a Deer that “I am forever/telling my kids I don’t know.” (p.102). In a world filled with false certainties, this admission is both humbling and reassuring.

In Dad Jokes from Late in the Patriarchy Huey moves us through the basics of contemporary poetic humor and irony into a depth where the pressure of his observation is reduced to dark statements of fact-based reality. Unflinching in his inquiry, his humor is masterful and self-deprecating—letting us into his own battered persona. He understands the power that humor can have in truth-telling, however individualized that truth-telling must be. At its best poetry creates in us a vicarious identity that transcends ourselves into the voice of the poet we are reading. In Dad Jokes from Late in the Patriarchy Huey creates that vicariousness through the authenticity of a father struggling through these modern times and ultimately struggling with the self within those times. If the conclusion of Huey’s inquiry in this collection is an embrace of intellectual agnosticism, then perhaps we should consider joining him and learn to un-know those things when we are at our most certain.